Budgeting for Capital Expenditures in Multifamily Acquisitions

Budgeting for capital expenditures (CAPEX) is critical to any real estate analysis. The most astute multifamily investors I work with will hire an inspector in the due diligence phase of purchasing a property. The investor and the inspector will walk through all units, review the mechanicals, look at the foundation, roof, and exterior, and list all necessary repairs to maintain the property's structural integrity.

Contents

Capital Expenditures Definition

CAPEX is the big-ticket repairs and replacements. Usually, these expenditures will happen infrequently but be more costly than ordinary operating expenses.

Let's take an old, bumpy parking lot as an example. It's been a maintenance nightmare. You can patch all the potholes or replace the entire lot.

Perhaps historically, you've been patching potholes annually to keep the lot functional. After a snowy winter, the plowing and salting result in re-patching every spring. The repetitive nature of this method makes this expense OPEX. If you were to replace the lot entirely, your accountant would likely classify this as CAPEX.

CAPEX Classification

Using the same example as above, let's say patching vs. complete replacement costs something like:

Patching Annually: $2,500

Replacement: $45,000

Because the patching is OPEX, you can deduct that expense for tax purposes. If you decide to move forward with a complete replacement, the IRS will not just let you deduct $45,000 in one tax year! They will take the $45,000, divide it by the useful life of the improvement, and you would be able to take a depreciation deduction over that period. If you determined the useful life to be 15 years, the annual depreciation deduction would be $45,000/15 = $3,000 annually.

Disclaimer: I am not an accountant, and your CPA should determine the minutiae of the CAPEX classification.

When I'm looking at a property for a client, I will classify the following repairs as capital expenses.

Exteriors

Roof Replacement

Siding Replacement

Tuck-pointing (on older buildings)

Landscaping

Window Replacement

Major Structural Repairs (Foundation/Parking Structures)

New Gutters/Fascia/Soffits

Mechanicals

Boiler Replacement

New Water Heaters

Electric - New Breakers/Panels

Electric - New Wiring

Plumbing Upgrades

Interiors

Flooring Replacement

New Appliances

Remodeled Kitchens

Remodeled Bathrooms

Carpet/Paint in certain instances

Hardware/Lighting/Plumbing Fixtures

CAPEX Budgeting

In an underwriting analysis, I will use four common ways to fund the monies necessary for CAPEX projects.

Raising CAPEX Funds Upfront

Raising funds for CAPEX is the most common approach I've seen. Typically, the purchaser of an apartment building will get the financing secured as a percentage of the asset's value (commonly referred to as loan-to-value or LTV). From there, they will create a capital expenditure budget and raise that required money from investors upon closing.

Let's say a property costs $2,000,000. The buyer secures agency financing at 75% LTV ($1,500,000 loan) and expects the capex budget to total $150,000.

The buyer would need to bring $650,000 in equity to the closing table (excluding closing costs and borrowing costs)

$500,000 in cash to purchase the property

$150,000 in cash to fund the CAPEX.

Financing CAPEX

I've seen this scenario commonly when an investor purchases a multifamily property with significant deferred capital and is distressed. Some loan programs allow you to borrow funds as a percentage of the total cost (the property value plus capital investment). This arrangement is commonly referred to as loan-to-cost (LTC).

Our Redevelopment Model is best equipped to handle a messy repositioning effort and has features that allow the investor to:

Elect whether you will finance construction costs (LTC or LTV possible)

Flexibility with the lender's interest reserve requirement

Using the same example above, the buyer would get 75% financing on the total cost of the property. The buyer would need to bring $537,500 in equity to the table.

($2,000,000 + $150,000) * (1 - 75%) = $537,500

Suppose repairs and improvements are more cosmetic, but the lender is willing to finance the construction costs. In that case, the Value-Add Model could be a helpful tool for project evaluation. However, you'd need to make a minor adjustment to the model to account for the LTC financing assumption.

Funding CAPEX with Cash Flow

Counting on cash flow is the riskiest approach because you are not funding any capital investment with outside equity or financing. This method should be reserved for the most experienced investors or institutional entities that buy properties in cash or use minimal leverage. If the ordinary investor utilizes this approach, one slip-up in the business plan could make it challenging to take care of deferred capital. Depending on the nature of the repairs, the property could be vulnerable and obsolescent.

Combination of Methods

I have heard of syndicators and other experienced investors often raising only a portion of the equity needed for capital expenditures and then counting on cash flow for future repairs. A typical instance where this method is used is for in-unit renovations. Only a portion of the rehab capital is raised on the front end. The rental premiums associated with rehabbing units can then be used to fund future improvements of other units or a deeper value-add later in the investment hold.

CAPEX Budgeting Effect on Proforma

The method you choose will significantly impact the real estate investment metrics. The less cash you need upfront correlates with higher returns on the back end. Therefore, someone utilizing cash flow to fund CAPEX will achieve a higher IRR and equity multiples than if they were to inject the CAPEX proceeds at closing.

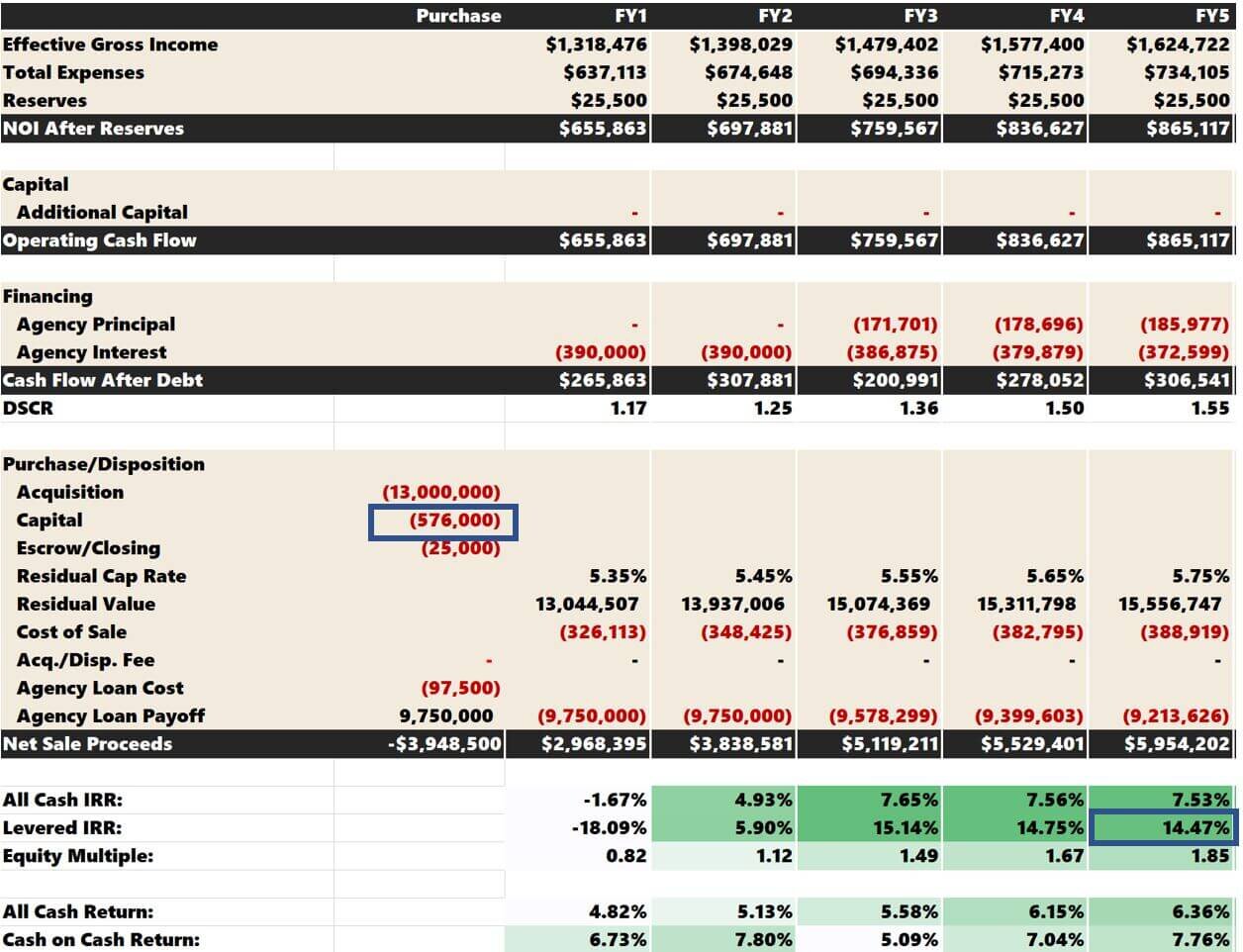

Let's say we are looking at an 85-unit value-add property. The price point is $13,000,000, and after doing unit inspections, it's determined that $576,000 is needed in additional capital to renovate all units.

100% of CAPEX Raised By Investors

We will assume that all renovation capital is raised from investors on the front end (but not financed).

The Summary of Proceeds is the following:

Let’s take a look at the returns on a five-year hold.

You can see from the “Return’s Summary” that capital is accounted for as $-576,000 in Year 0, and the levered IRR is 14.47%.

100% of CAPEX Paid With Cash Flow

Now, instead of raising the CAPEX on the front end, let’s roll the dice and assume we are funding the renovations with cash flow.

Now, the summary of proceeds looks like this:

The Equity Needed to fund the deal drops significantly from our first example. Again, let’s look at the “Return’s Summary:”

The capital expense is spread out over the years (-$192,000 per year) and is fully funded by cash flow. No capital is raised on the front end, and the IRR jumps from 14.47% to 15.40%, almost a 100 basis point increase.

It’s also important to note that the financing assumption includes two years of interest-only (IO) in this example. Not paying interest during the renovation years is a massive help for deal sponsors and, in this instance, assures that cash flow stays positive even after funding the rehabs.

Notice that the “Cash Flow After Debt” in FY3, once the IO term runs out, is only $8,991. There is not much margin for error. If something adversely affects operations, you may need to depend on a capital infusion from somewhere (perhaps via the dreaded “capital call”).

Summarizing Multifamily CAPEX

I didn’t realize how much the CAPEX funding strategy could impact the returns. In the brokerage world, where I gained experience, we assumed renovations were funded with cash flow. As you see above, this boosts the returns.

There were many instances where I talked with acquisitions analysts about why their returns didn’t match our projections. The disconnect was that their leveraged IRR was usually lower than we were forecasting. We would comb through the operating revenues, expenses, and value-add program, have identical underwriting assumptions, and still be off base.

In their model, they were raising CAPEX on the front end, and our team was funding CAPEX with cash flow. Since we were talking to multiple groups with infinite funding strategies, this was a sensible way for us to go about it because it was a wide-ranging, consistent approach. Every ownership group had its unique method of accounting for CAPEX. I would have saved a lot of time and effort if my first question to them was asking about their funding strategies.

I believe raising CAPEX funds upfront is the prudent, conservative approach. Planning on property cash flow to fund CAPEX should be reserved for the most experienced ownership groups.